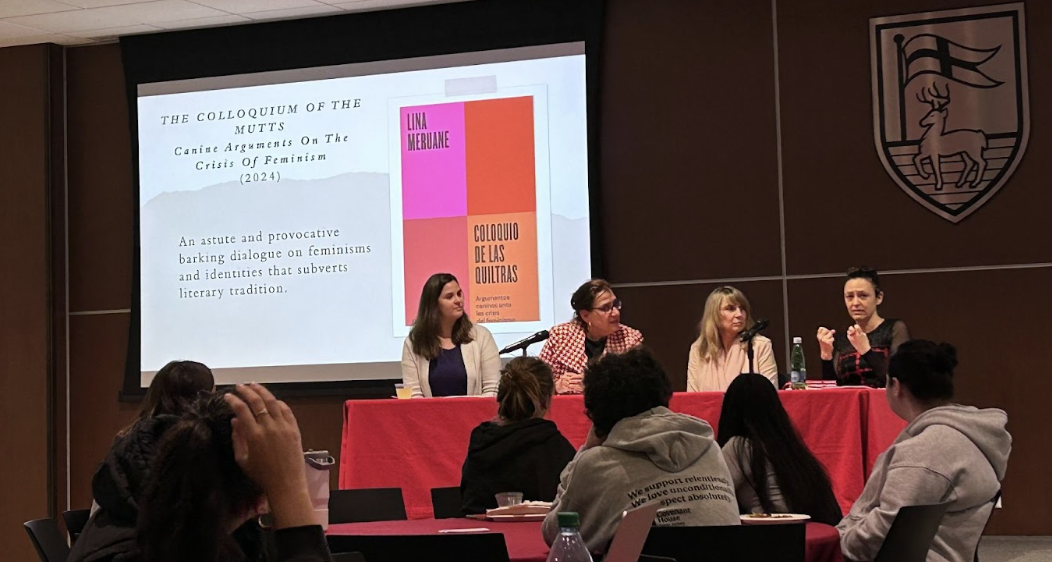

In the current political climate, in which students who write op-eds that critique the war in Gaza and are subsequently arrested and deported, Fairfield University hosted Chilean-Palestinian writer Lina Meruane for an evening of reflection, memory and resistance in the Barone Campus Center. Titled “Chilestinians: Notes on the Palestinian Diaspora in Chile,” the event was more than a literary talk, it was a rare and timely moment of engagement with questions of exile, erasure and identity that reverberate far beyond Chile and Palestine.

Meruane, author of “Seeing Red” and “Nervous System,” spoke with searing clarity about the fragmented histories and layered identities that mark the Palestinian diaspora in Latin America, particularly in Chile, home to the largest Palestinian community outside of the Middle East. Her words cut through the abstraction of global politics, grounding the audience in lived experiences, of migration, assimilation, loss and the will to remember. With a style that was both intimate and intellectually urgent, Meruane described how Palestinians in Chile, many of whom arrived fleeing hardship under Ottoman rule in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, faced racialized exclusion in Latin America. They were renamed, othered and pushed toward assimilation. “For every small village in Chile, there were three things: a policeman, a pastor and a Palestinian,” she recounted. Yet the price of belonging was high; families shed their native Arabic, converted faiths and silenced the language of their homeland, a silence that, as Murane emphasized, “only came out in their dreams.”

But silence is not the whole story. In a world where the Palestinian narrative is so often suppressed or simplified, Murane’s presence reminded us that culture survives: in literature, in soccer teams named “Palestino,” in community and in memory. The evening’s discussion touched on the idea that writing, for displaced people, can become a difficult yet essential home. “Can writing be a home?” someone asked. “It’s a contradictory one, full of love and hate, but it’s close to our hearts.”

Meruane also shared the very real challenge of telling Palestinian stories in today’s media landscape. She spoke candidly about self-censorship, public backlash and the fear that creeps in even in academic or literary spaces. Yet, her voice, clear, firm and compassionate, was a reminder that to speak is, in itself, an act of defiance. “Power always directs its punishments to the people,” she said. “But I want to carry the stories of the people.”

The conversation, led by Fairfield University faculty and followed by a lively audience Q&A, wove together threads of gender, colonialism and her art of writing. The audience learned about Meruane’s feminist roots, shaped by the image of her grandmother, a rare woman law graduate in a sea of men, and her commitment to telling complex stories that do not cater stereotypes or erasures.

In a global moment when the question of Palestine is not just contested but actively silenced, Meruane’s voice is one we need more than ever. Her work challenges us to reject the illusion of assimilation as success and instead embrace multiplicity, memory, and the right to return, physically, linguistically and culturally. The event was a powerful reminder that history does not disappear just because borders shift. And while “the old may die,” as Meruance quoted, “the young do not forget.”

As violence escalates in Gaza and headlines become numbingly repetitive, moments like this, of listening, of witnessing, of refusing to forget, matter deeply. They remind us that Palestine is not only a place but a people. And those people, wherever they are, in Ramallah, in Santiago, or at Fairfield University deserve to be heard.