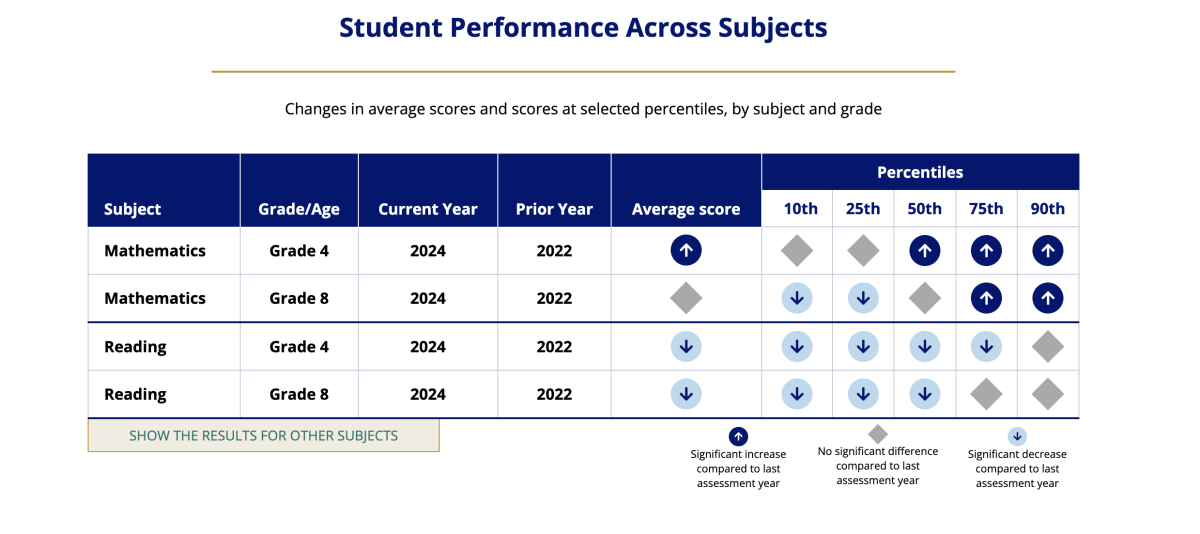

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the world – but especially the United States – has been plagued by stunning decreases in literacy and comprehension among students. The 2025 National Report Card index displayed the lowest levels of literacy since 1992, with a widening gap between the best and worst performing students. The pandemic confining students to a precarious learning environment and failures to adjust likely form part of this phenomenon, but could there be a deeper institutional cause?

Throughout the 2000s up to the mid-2010s, the state of Mississippi consistently placed last in education, literacy and reading comprehension in national experiments. This phenomenon was so renowned that it coined a jeering phrase across other low-scoring states: “Thank god for Mississippi!” In recent years, however, there’s been a turnaround which some have called the “Mississippi Miracle”. The reintroduction of phonics-based education caused Mississippi to jump from the 49th worst state for student reading comprehension, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress in 2013, to the 21st best in 2022.

Phonics is the practice of teaching children language by having them sound out parts of a word as they write to build a connection between the spoken word and the written language at an early age. Among educators, there’s been a longstanding debate over whether phonics or “whole language” practices, which is the notion that language is a maturational feature that comes naturally to humans and doesn’t need to be induced with such specificity, is better at achieving literacy. Around the 1990s, many schools abandoned phonics in favor of the more concise whole language approach, but ever-worsening reading scores indicate they made the wrong gamble.

There have been a myriad of consequences of “whole language” learning: students struggling to transfer the written word to their brains develop limited capacity for reading or understanding texts, hindering academic performance later in life. If a child declares that they hate reading, it might be because their teachers have failed to provide them with the capacity to understand the text. This has also negatively impacted media literacy, as if one struggles to transfer the latent text to their conscious mind, how can they pick up on deeper themes, literary conventions, or subliminal meanings in books, TV and movies?

Challenges to literacy have also shown themselves in changes to everyday speech. Various malapropisms have become mainstream in not only online discourse but even esteemed publications. The word “infamous”, which refers to someone or something well known for negative qualities, has seen interchangeable use with its antonym “famous”. The word “bemused” has been used as a synonym for “amused”, when it’s actually a synonym of “confused”. In August of this year, the magazine Variety had to delete a tweet reading that “Guillermo del Toro casted Jacob Elordi as Frankenstein” following a cavalcade of tweets bemoaning the increasing use of the non-existent word “casted” as a past-tense for “cast”, which is unaltered across all tenses.

Some will argue that these are the result of natural evolution in language, and it’s not worth any concern. Perhaps this argument has weight for petty grievances such as overusing the word “literally”, but there are cases where it can literally lead to genuine problems, namely when medical lingo gets thrown around haphazardly. On social media, people have made a habit of describing their inner desires as “intrusive thoughts”, a term usually reserved for extreme, baseless fears associated with disorders such as OCD and schizophrenia. By appropriating the term to refer to an impulsive desire for pleasure, it leaves those who suffer from impending fears that they might commit a crime or be in serious danger without a word to communicate their issues in a manner that most will understand.

Obviously, it’s unrealistic to ask everyone to have a Hemingway level of vocabulary, and overutilization of ostentatious verbiage can exhibit itself as equally vacuous and wearisome as a limited vocabulary. Still, the consolidation of language into a finite number of basic words is a worrying prospect, for when life is so boundless with emotion, why should we constrain how we describe our experiences? Moreover, why should the nation’s children grow up averse to reading and engaging with art because their early education favored shortcuts over truly uplifting them? By nationally mandating comprehensive teaching of phonics, we can rebuild the general population’s vocabulary, have more engaging conversations about stories and better express ourselves, feats more than worth striving for.